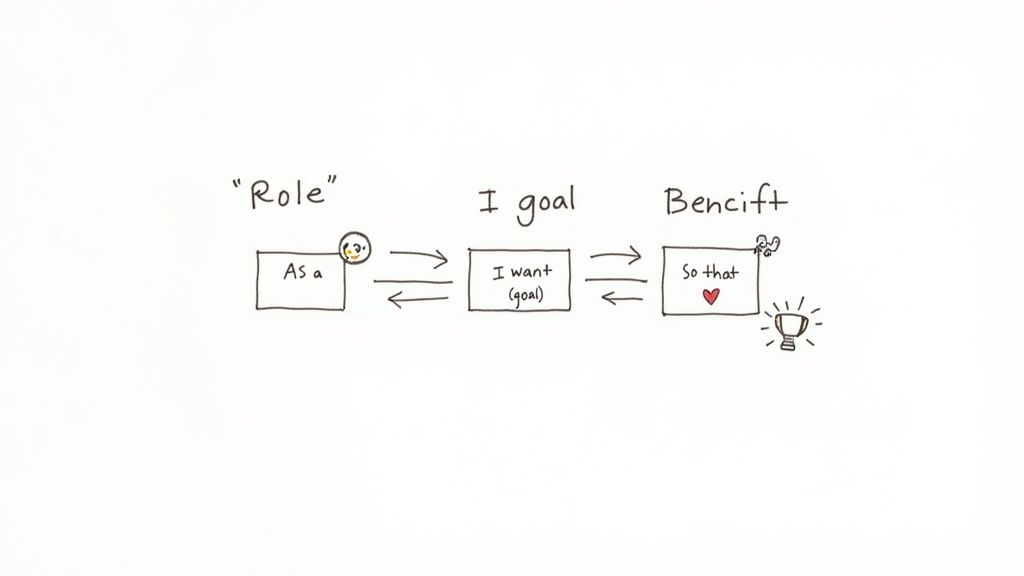

At its heart, an agile story is a simple, user-focused requirement written in a classic format: “As a [role], I want [goal], so that [benefit].” This isn’t just a template; it’s a fundamental shift in mindset. It forces every piece of development work to be tied directly to real user value, moving teams away from building technical tasks and toward solving actual problems.

Why Better Agile Stories Will Transform Your Team’s Performance

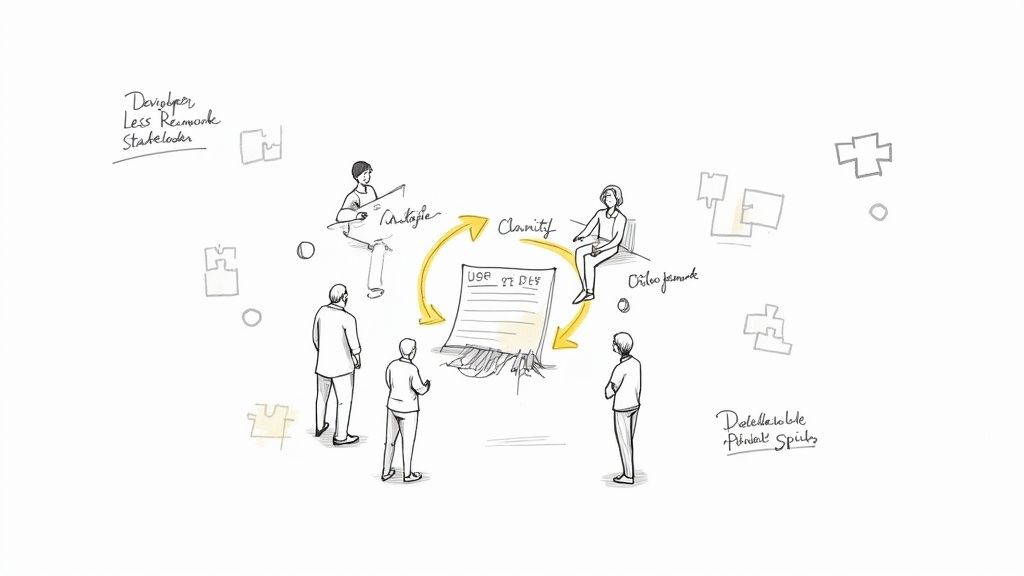

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, it’s worth stopping to appreciate the real-world impact here. Well-crafted agile stories do a lot more than just fill up a backlog. They are the very foundation of efficient, value-driven development.

When done right, they slash ambiguity, cut down on rework, and create a shared mission that pulls developers, designers, and stakeholders together. This isn’t just about better paperwork—it’s about building a framework for success.

The results are almost immediate. Sprints become more predictable. Delivery cycles get shorter. Team morale actually improves because the clarity from a great story means less time is wasted in endless meetings debating what to build, and more time is spent building things that matter.

The Power of a Shared Understanding

Think of a user story’s primary job as starting a conversation. It’s the single source of truth that gets the entire team on the same page about a specific user need. This shared context is absolutely vital for making smart implementation decisions later on.

When a developer truly gets the why behind a feature, they can often suggest far more efficient or elegant technical solutions. This collaborative spark is a core part of building a strong product, a process you can dive deeper into in our guide to continuous product discovery.

The benefits of a standardised approach are also crystal clear. A recent survey of 420 development teams in Southeast Asia found that simply adopting a consistent user-story template reduced their story-grooming time by an impressive 28%. It also cut the number of teams affected by sprint-planning overruns from 22% down to just 9% within six months. You can check out the full survey findings on regional IT outsourcing trends on coaio.com.

A user story is not a detailed specification. It’s an invitation to a conversation. This shift in mindset empowers teams to collaborate on the best possible solution rather than just executing a rigid set of instructions.

Ultimately, mastering the art of the agile story is a seriously high-leverage skill. It directly impacts your team’s ability to ship the right features, faster.

Now, before we break down how to write them, let’s look at the core components in a quick-reference table.

The Anatomy of an Effective Agile Story at a Glance

This table gives you a quick summary of the core components that make up a high-quality agile user story. We’ll be exploring each of these in much more detail throughout the guide.

| Component | Purpose | Key Question It Answers |

|---|---|---|

| User Persona | Defines who the user is. | ”Who are we building this for?” |

| Goal/Action | Describes what the user wants to do. | ”What does this person want to achieve?” |

| Benefit/Value | Explains why the user wants it. | ”What’s the motivation behind the goal?” |

| INVEST Criteria | Acts as a quality checklist. | ”Is this story well-formed and ready for development?” |

| Acceptance Criteria | Defines the conditions of satisfaction. | ”How will we know when we’re done?” |

Think of this table as your cheat sheet. As we go through the next sections, you’ll see how each piece fits together to create a story that is clear, actionable, and valuable.

Building Your Story with the Role Goal Benefit Formula

Let’s talk about the classic formula that powers every great user story: As a [Role], I want [Goal], so that [Benefit]. This isn’t just a template to fill in; it’s a powerful little framework that forces you to put the user at the centre of every decision.

Think of it as the core DNA of a story. It tells your team who they’re building for, what that person is trying to do, and most importantly, why it even matters. Get these three parts right, and you’ve created a shared understanding that sparks the right conversations from the get-go.

If you want a deeper dive into the fundamentals, this guide on how to create effective user stories is a great resource. For now, let’s break down each piece with some real-world examples.

Nail the Role: Be Specific

First up is the [Role]. This is where you define your user persona, and honestly, it’s where most teams stumble. A role like “user” or “customer” is practically useless—it tells your development team absolutely nothing. You have to get specific to build empathy.

Who are you really building this for? Is it a “new trial user” trying to see the value? A “power user with multiple projects” who lives in your app all day? Or maybe an “administrator managing team permissions”? Each of these personas has wildly different needs.

- Weak Role: As a user…

- Strong Role: As a freelance designer managing multiple client projects…

See the difference? That level of detail instantly frames the problem. A freelance designer has different pressures than a project manager in a huge corporation. Getting this specific helps the team actually visualise the person they’re helping, which is the cornerstone of successful customer needs identification.

Define a Clear, Actionable Goal

Next is the [Goal], which describes what the user wants to accomplish. The key here is to keep it concrete and focused on the user’s desired outcome, not the technical solution. It’s the “what,” not the “how.”

Steer clear of vague goals like “manage files.” What does that even mean? A much better goal would be something like “quickly find a specific invoice by client name” or “archive a completed project to clean up my dashboard.”

A great goal describes an interaction with the system from the user’s perspective. It should be an action that moves them closer to achieving their overall objective.

Let’s look at an e-commerce example:

- Weak Goal: …I want to see products…

- Strong Goal: …I want to filter products by colour and size…

The second one is instantly actionable. The dev team knows exactly what they need to build. No guesswork involved.

Connect Everything to a Meaningful Benefit

Finally, we have the [Benefit]. This is the “so what?” and, in my opinion, the most critical part of the whole story. It’s where you tie the feature directly to the value it provides the user, giving the team purpose and motivation.

A common trap is making the benefit about the system, like “…so that the database is updated.” That’s not a user benefit. The benefit must always, always be from the user’s point of view.

Let’s put all three pieces together for a typical SaaS product.

- Poorly Written Story: As a user, I want a button, so the system can save data.

- Well-Written Story: As a project manager on a deadline, I want to save my report with a single click, so that I can quickly share progress with stakeholders without losing my work.

The second version is worlds better. It gives the team a clear persona to empathise with, a specific action to build, and a compelling reason why it all matters. That clarity is what turns a simple task into a genuinely valuable piece of work.

Using the INVEST Criteria to Stress-Test Your Stories

Okay, so you’ve nailed the “Role-Goal-Benefit” format. That’s a brilliant start, but it doesn’t automatically mean a story is ready for your development team to pick up. Think of what comes next as a quick quality control check before anything hits a sprint.

This is where the INVEST criteria come into play. It’s a simple but incredibly powerful framework to stress-test every single story.

The acronym stands for Independent, Negotiable, Valuable, Estimable, Small, and Testable. Running a story through these six filters is the best way to make sure it’s clear, feasible, and genuinely ready to go. It’s how you move from just writing stories to building a predictable, efficient workflow.

Independent and Negotiable Stories

First off, a story should be Independent. This means your team can develop and deploy it on its own, without it being tangled up with a bunch of other stories. When stories are heavily dependent on each other, you’re just creating bottlenecks. If story A has to be finished before story B can even begin, you’ve just introduced a massive risk to your sprint’s success.

The goal is to slice stories vertically to break those dependencies. Instead of a monster story like “User Profile Overhaul,” you’d create smaller, independent pieces like “Add Profile Picture Upload,” “Update Contact Information Form,” and “Implement Privacy Settings.” Each one can be built and shipped on its own.

A story also has to be Negotiable. It’s not a rigid contract signed in blood; it’s a conversation starter. The initial story provides the context—the what and the why—but the how should be hammered out through collaboration between the product owner, developers, and designers. This flexibility is key because it empowers the team to find the best possible solution, not just the first one that was written down.

Valuable and Estimable for Clear Impact

This one feels obvious, but you’d be surprised how often it gets missed. Every story must deliver tangible Value to the end-user or the business. If you can’t clearly articulate the “so that” benefit, the story probably shouldn’t be a priority. This principle forces you to constantly ask: are we building features, or are we solving real problems?

A story like “Optimise database queries” is a classic example of a task, not a user story. It has no user value on its own. A much better, value-driven version would be, “Improve dashboard loading speed so that users can access their data faster.” Now we’re talking.

On top of that, your development team has to be able to Estimate the effort required. If a story is too vague or way too big, any estimate is just a wild guess. Something like “build a reporting engine” is impossible to estimate. The story needs to be broken down and refined until the team can confidently assign story points to it. This isn’t just about ticking a box; it’s fundamental for sprint planning and predictability.

An un-estimable story is a giant red flag. It’s a signal that you don’t understand the problem well enough yet. It means you need more conversations, not a bigger sprint.

Small and Testable for Focused Delivery

Good stories are Small. They need to be granular enough that they can be completed comfortably within a single sprint, ideally in just a few days. Large, chunky stories (often called epics) are notorious for derailing sprints because hidden complexities always crawl out of the woodwork mid-development.

Keeping stories small reduces risk and creates a steady, satisfying stream of completed work. Little wins build momentum and are fantastic for team morale.

Finally, every story must be Testable. This just means you can objectively prove when it’s done. This is exactly what acceptance criteria are for. If you can’t define clear, binary (pass/fail) conditions for success, you can’t build it properly, and you definitely can’t test it.

“The page should look better” is completely untestable. In contrast, “The primary call-to-action button must be colour #cb58f9 and located in the top-right corner” is perfectly testable. This simple clarity ensures everyone on the team has the exact same definition of “done.”

INVEST Checklist From Theory to Practice

To help bring all this together, think of it as a checklist. Before you finalise a story, run it through this quick comparison to see if it holds up. It’s a great way to spot anti-patterns before they make it into your backlog.

| INVEST Principle | Weak Story Example (Anti-Pattern) | Strong Story Example (Best Practice) |

|---|---|---|

| Independent | As a user, I want to update my profile picture, but it depends on the new cropping tool story being done first. | As a user, I want to upload a new profile picture so I can personalise my account. |

| Negotiable | As a user, I want a dropdown menu with exactly these five options, built using the React-Select library. | As a user, I want to select my country from a list so I can enter my address correctly. (The team will decide the best UI.) |

| Valuable | As a developer, I want to refactor the authentication service. | As a customer, I want to log in with my Google account so I don’t have to remember another password. |

| Estimable | As a manager, I want a new analytics dashboard. (Too big and vague.) | As a manager, I want to see a bar chart of daily sign-ups on my dashboard so I can track user growth. |

| Small | As a user, I want a complete shopping cart feature with payment, shipping, and order history. (This is an Epic.) | As a user, I want to add an item to my shopping cart so I can purchase it later. |

| Testable | As a user, I want the checkout process to feel faster and more intuitive. (Subjective.) | As a user, I want to see a confirmation message (“Payment Successful”) within 2 seconds of clicking the “Pay Now” button. |

By consistently applying the INVEST criteria, you’re not just writing better stories; you’re building a healthier, more predictable development process. Your team will thank you for it.

Writing Acceptance Criteria That Actually Work

If the user story is the “why,” then Acceptance Criteria (AC) are the “what.” This is where a good idea sheds its ambiguity and becomes a concrete, shippable feature.

Without clear AC, your development team is basically flying blind. This inevitably leads to misunderstandings, frustrating rework, and the dreaded “well, it works on my machine” conversation. Nobody wants that.

Well-written AC are the ultimate definition of “done.” They serve as a clear checklist of conditions that must be met for the story to be considered complete, leaving absolutely zero room for interpretation. This empowers your developers to build with confidence and lets your testers validate with surgical precision.

Ultimately, good AC act as a contract between the product owner and the development team. They forge a shared understanding of the expected outcome before a single line of code is ever written.

From Simple Checklists to Detailed Scenarios

Acceptance criteria can come in a few different flavours, and the format you choose often depends on the complexity of the story you’re writing. For straightforward features, a simple checklist usually does the trick.

For a story about a password reset feature, your AC might look something like this:

- The user must enter a valid, registered email address.

- A password reset link is sent to that email address.

- The link must be valid for 24 hours.

- Clicking the link takes the user to a “Create New Password” screen.

This rule-oriented format is simple, scannable, and perfect for stories with clear, binary outcomes. Each bullet point is a testable condition. Think of it like a simplified version of a good bug report; you can even pull inspiration from a well-structured bug report template when thinking about conditions and expected results.

Using Gherkin for Complex User Flows

For more complex stories involving multiple steps or user interactions, a scenario-based format called Gherkin is incredibly effective. It uses a Given-When-Then structure to describe behaviour without getting bogged down in technical jargon.

- Given: Some initial context or precondition.

- When: A specific action is performed by the user.

- Then: The expected outcome or result of that action.

Let’s apply this to a shopping cart story: As a returning customer, I want to see items from my last session in my cart, so that I can easily continue my shopping.

Scenario: Customer returns to the site with items in their cart Given I am a logged-in user with 2 items in my cart And I have left the site for more than 30 minutes When I return to the homepage Then I should see a “2” on the cart icon And when I click the cart icon, I see the 2 items from my previous session

This format is brilliant because it forces you to think through the user’s journey step by step. It’s also easily understood by everyone on the team—developers, testers, and even non-technical stakeholders. If you want to see these principles in action, reviewing some concrete examples of user stories with acceptance criteria can provide great inspiration.

Don’t Forget Non-Functional Requirements

Finally, great AC cover more than just user-facing functionality. They should also address non-functional requirements like performance, security, and accessibility. These are often overlooked but are absolutely critical for a good user experience.

- Performance: The user search results must load in under 500ms.

- Security: All password fields must encrypt user input.

- Accessibility: All form fields must have corresponding labels for screen readers.

By including these in your AC, you ensure that quality is built in from the start, not just bolted on as an afterthought. This holistic approach is essential when writing an agile story that leads to a robust and well-rounded feature.

Turning Raw Feedback into Actionable Stories

Let’s be honest, customer feedback rarely shows up gift-wrapped. It’s usually messy, emotional, and scattered across support tickets, survey replies, and community forums. The real art is building a reliable system to catch this raw insight and methodically turn it into a backlog-ready story.

This is where you bridge the gap between just listening to users and actually acting on what they tell you. Without a clear workflow, great ideas get lost in the noise, and your roadmap slowly drifts away from what customers truly want. A structured approach ensures every good idea gets a fair shot.

From Messy Feedback to a Prioritised Ticket

Imagine a customer fires off some feedback through a widget, like one from HappyPanda. It might just say, “It’s annoying that I can’t find old invoices for my tax returns.” That’s your starting point—a genuine pain point. The very first step is to get this into your project management tool, like Linear, as a preliminary ticket.

This first ticket doesn’t need to be perfect. Its only job is to capture the essence of the problem. You might title it: “Allow users to search/filter their invoice history.” This creates a central hub for collecting any related feedback and stops duplicate requests from clogging up your system.

The goal here isn’t to write the final story. It’s about centralising the conversation and making sure the raw user voice is documented before anyone starts refining it.

Think of this as crucial triage. You’re moving a fleeting comment from a temporary inbox into a permanent system of record, getting it ready for the next stage: collaboration.

Refining and Structuring the Story

Once that initial ticket is logged, the product owner can start shaping it into a proper agile story. This should always be a team effort. They might sync up with the support agent who first flagged the feedback or post in a dedicated Slack channel to get early thoughts from designers and engineers.

You can make this seamless with simple automations. For instance, set up a rule where creating a “feature request” ticket in Linear automatically pings a #product-feedback channel in Slack. This keeps the right people in the loop without you having to remember to do it manually.

Through this conversation, the team starts to flesh out the story:

- Role: Who are we really building this for? “A small business owner preparing quarterly taxes.”

- Goal: What do they actually need to accomplish? “I want to search my invoice history by date range.”

- Benefit: Why should we care? What’s the payoff? “So that I can quickly find and export the documents I need for my accountant.”

This process adds the critical context, turning a vague complaint into a clear, value-driven objective. The team can hash out potential complexities, clarify the scope, and start thinking about acceptance criteria, making sure everyone is aligned before a single line of code is written. Just like that, raw feedback becomes a focused, actionable piece of work.

Common Story-Writing Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Even seasoned teams can stumble into a few classic traps when writing agile stories. Spotting these anti-patterns is the first step to keeping your backlog clean, effective, and actually useful. Think of this as your field guide for troubleshooting stories that just don’t feel right.

One of the most common blunders? Writing a technical task and trying to pass it off as a user story. These impostors offer zero user value and get bogged down in implementation details. If you see a story starting with “As a developer…,” that’s a huge red flag.

- Before: As a developer, I want to add a new index to the

invoicesdatabase table. - After: As a finance manager, I want to load the invoice history page in under two seconds, so that I can find client records without delay.

See the difference? The “after” version zeroes in on the user’s actual problem (painfully slow load times) and the benefit they’ll get (speed!). This gives the development team the freedom to decide if a database index is the best fix or if there’s a smarter way to solve it.

Spotting Stories That Are Actually Epics

Here’s another classic pitfall: writing stories that are just way too big. If a story looks like it’ll take more than a few days for a pair of developers to complete, you’ve probably got an epic on your hands—a whole collection of related stories masquerading as one. Trying to cram an entire epic into a single sprint is a surefire recipe for missed deadlines and a whole lot of frustration.

- Before: As a new user, I want to set up my entire account profile.

- After:

- Story 1: As a new user, I want to upload a profile picture, so I can personalise my account.

- Story 2: As a new user, I want to add my billing information, so I can subscribe to a plan.

By breaking that behemoth down into smaller, bite-sized stories, the work becomes manageable. Better yet, you can deliver a steady stream of value instead of making users wait for the whole feature.

Finally, let’s talk about vague acceptance criteria. A well-intentioned story can be completely derailed by fuzzy, untestable conditions. Without a clear definition of what “done” looks like, it all becomes a matter of opinion.

Before AC: The user should find the new feature easy to use. After AC: When the user clicks “Export,” a CSV file is generated and downloaded within three seconds.

The corrected version is specific, measurable, and leaves no room for confusion. It gives developers a clear target to hit and QA a straightforward test case, ensuring everyone is on the same page about what success actually means.

Ready to turn messy customer feedback into perfectly formed agile stories? HappyPanda gives you the tools to capture, organise, and act on user insights, all in one place. Start your free trial today.